1. What are determiners in English?

Determiners in English are small words that sit before a noun to tell your reader (or listener) which thing you mean, how many there are, or who it belongs to.

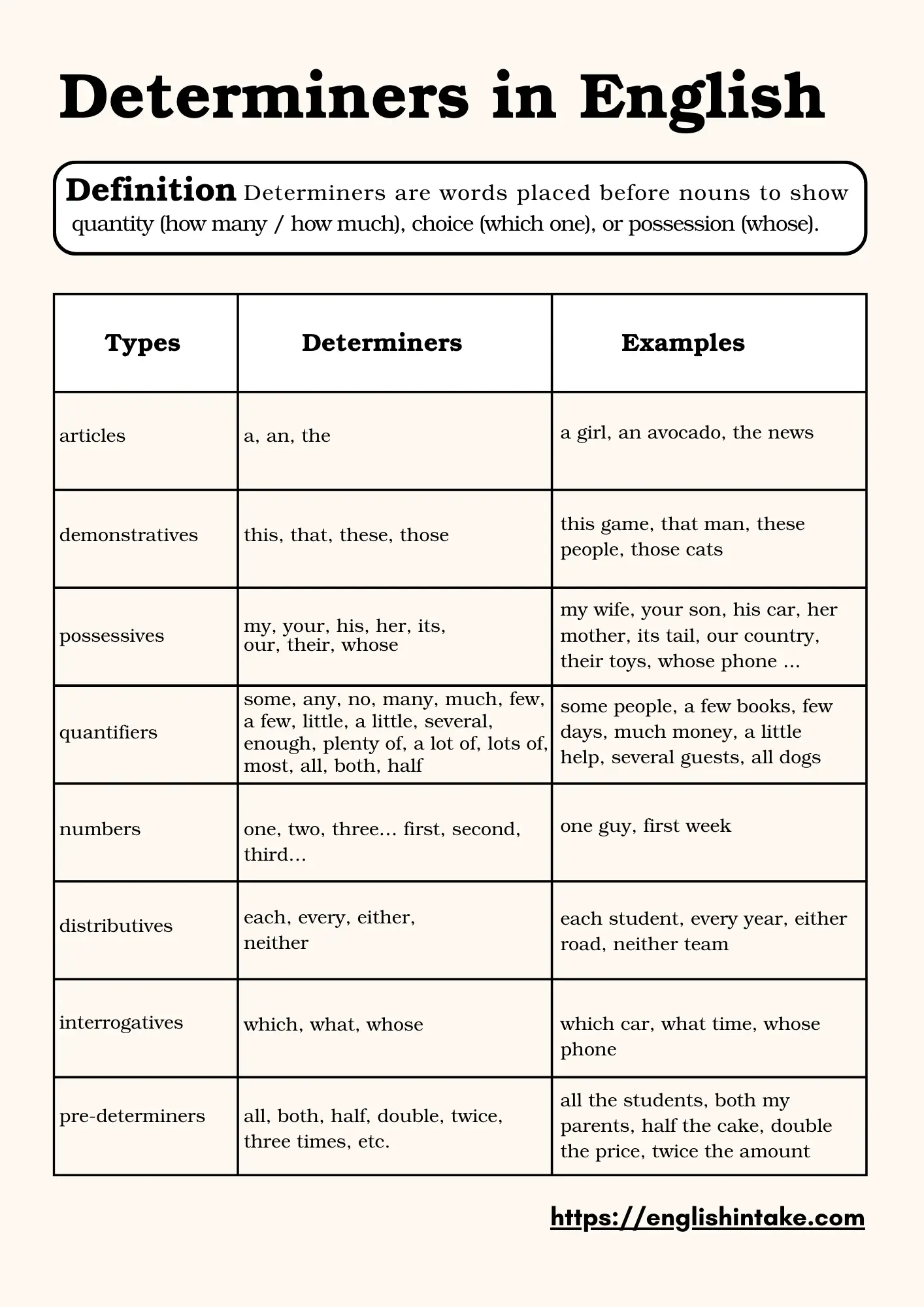

Here is a list of determiners in English.

- Articles

- Demonstratives

- Possessive pronouns

- Possessive names (’s)

- Question words

- Distributives

- Predeterminers

- Quantifiers

- Numbers

This guide helps you learn types of determiners, explain how they work with different kinds of nouns, show you common mistakes, and teaches you to choose the right determiner to use.

2. Role

A determiner specifies something about a word placed before a noun (or before any adjectives that describe that noun). It might tell you whether the noun is specific or general, how many there are, or whose it is. In the phrase "my three old books," the words my and three are determiners.

In most cases, a singular countable needs a determiner. You can say "dogs are loyal" (plural, no determiner needed), but you cannot say "dog is loyal." You need "a dog is loyal" or "the dog is loyal."

3. Types of determiners in English

3.1 Articles

Articles are the most common determiners in English. There are three articles in English: a, an, and the.

The is the definite article. You use it when both you and your listener (or reader) know exactly which noun you are talking about. This might be because you have already mentioned it, because there is only one of it, or because the context makes it obvious.

| Example | Why "the" is used |

|---|---|

| I bought a shirt. The shirt was blue. | Already mentioned (second reference) |

| The sun rises in the east. | Only one sun; shared knowledge |

| Please close the door. | Context makes it obvious which door |

A and an are the indefinite articles. Use them when you introduce a noun for the first time or when you are talking about any member of a group, not a specific one. The choice between "a" and "an" depends on the sound that follows, not the letter. You say "a university" (because the "u" sounds like "yoo") but "an hour" (because the "h" is silent).

If the noun is singular, countable, and mentioned for the first time, use a or an. If the noun is already known to both speaker and listener, use the.

3.2 Demonstratives

The demonstrative determiners are this, that, these, and those. They point to a specific noun and show its distance from the speaker, either in physical space or in time.

| Determiner | Number | Distance | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| this | singular | near | This chair is comfortable. |

| that | singular | far | That building across the street is a library. |

| these | plural | near | These flowers smell good. |

| those | plural | far | I remember those days very well. |

The words "this" and "that" can also refer to time (this week, that afternoon, this evening). In writing, "this" and "these" can refer back to something that has just been mentioned, which is useful for keeping your text cohesive.

Be careful not to confuse demonstrative determiners with demonstrative pronouns. When you say "This is my bag," the word "this" is a pronoun (it replaces the noun). When you say "This bag is mine," the word "this" is a determiner (it sits before the noun "bag"). The same words do two different jobs depending on whether a noun follows them.

3.3 Possessives

Possessive determiners show who something belongs to. Some grammar books still call these possessive adjectives, but modern grammars treat them as determiners because they come before a noun.

- my

- your

- his

- her

- its

- our

- their

- whose

| Subject pronoun | Possessive determiner | Example |

|---|---|---|

| I | my | My train leaves at eight. |

| you | your | Is your sister coming? |

| he | his | His office is on the second floor. |

| she | her | Her presentation was brilliant. |

| it | its | The dog wagged its tail. |

| we | our | Our flight was delayed. |

| they | their | Their garden is beautiful. |

The most common spelling mistake here is confusing its (possessive determiner) with it's (contraction of "it is" or "it has"). The same problem shows up with your vs. you're, and their vs. they're. If you can expand the word into two words ("it is," "you are," "they are"), you need the apostrophe. If you cannot, you need the possessive form without one.

You cannot combine a possessive determiner with an article. Saying "the my book" or "a her friend" is not grammatical. A noun phrase takes one central determiner only.

3.4. Nominal genitive determiners ('s)

Nominal genitive determiners are formed by adding 's to a noun. In Emma's passport, Emma's occupies the same slot as "her" or "the". This construction is also called the Saxon genitive.

The form depends on how the owner noun ends. For most singular nouns, add 's (the manager's office, the dog's lead, a child's mistake). For plural nouns that already end in -s, add only an apostrophe (my parents' house, the students' essays). For irregular plurals that do not end in -s, add 's as normal: the children's coats, women's rights, people's opinions.

When a proper name ends in -s (James, Chris), British English generally favours adding 's and pronouncing the extra syllable: James's car /ˈdʒeɪmzɪz/. The apostrophe-only form (James') is also accepted, and tends to be preferred for classical names such as Socrates' philosophy or Moses' laws, where the added syllable feels unnatural.

The nominal genitive covers a range of relationships.

| Relationship | Example |

|---|---|

| Ownership | That is Sarah's laptop. |

| Association / role | The president's adviser resigned. |

| Authorship / origin | Have you read Atwood's latest novel? |

| Time expressions | Have you seen today's headlines? / She took two weeks' leave. |

| Organisations and places | The government's response was criticised. / London's transport network is vast. |

English has two genitive structures ('s and of). Use 's with people, animals, organisations, and time expressions; use of with inanimate objects. So you would say the teacher's explanation but the end of the road, the dog's bowl but the lid of the jar. When in doubt, "of" is the safer choice, though some inanimate nouns take 's in well-established expressions: the sun's rays, the Earth's atmosphere, the car's engine.

With joint ownership, only the last name takes 's: Tom and Sarah's flat (one shared flat). With separate ownership, both names take it (Tom's and Sarah's flats). When the owner is a whole phrase, the 's attaches to the final word of that phrase, not to the head noun:

- the King of England's speech,

- somebody else's umbrella,

- my brother-in-law's idea.

3.4 Quantifiers

Quantifiers tell you how much or how many. They include words like some, any, many, much, few, little, several, enough, no, all, most, both, and plenty of. Choosing the right quantifier depends on whether the noun is countable or uncountable.

| With countable nouns | With uncountable nouns | With both |

|---|---|---|

| many books | much water | some books / some water |

| few students | little time | any chairs / any money |

| a few mistakes | a little sugar | enough seats / enough space |

| several options | all the apples / all the rice | |

| a couple of friends | no cars / no information |

There is a subtle difference between few and a few, and between little and a little. Without the article, the meaning is negative (almost none): "Few people came to the party" suggests disappointment. With the article, the meaning is more positive (some, enough): "A few people came to the party" suggests it was a reasonable turnout.

Another common confusion is some vs. any. The general rule is that "some" appears in positive statements and offers ("Would you like some tea?"), while "any" appears in questions and negatives ("Do you have any questions?" / "I don't have any time"). There are exceptions, but this rule works well in most situations.

3.5 Interrogative determiners

There are 3 interrogative determiners in English.

- which

- what

- whose

Which asks about a choice from a known or limited set. For example, "Which colour do you prefer?" What asks about an open, unlimited set: "What colour is the sky?" Whose asks about possession (Whose jacket is this?).

3.6 Distributives

Distributive determiners refer to members of a group individually rather than as a whole. The main ones are each, every, either, and neither.

| Determiner | Used with | Example |

|---|---|---|

| each | singular countable noun | Each student received a certificate. |

| every | singular countable noun | Every seat was taken. |

| either | singular countable noun (two options) | You can sit on either side. |

| neither | singular countable noun (two options) | Neither answer is correct. |

"Each" and "every" are close in meaning but not identical. Each highlights individual members one by one ("each student" focuses on them separately), while every highlights the group as a complete set ("every student" means all of them, no exceptions). "Each" can be used for two or more; "every" requires three or more.

3.7 Numbers

Both cardinal numbers (one, two, three) and ordinal numbers (first, second, third) can function as determiners when they come before a noun. "I need three chairs" and "She finished in second place" are examples of numbers doing the work of a determiner.

Numbers are generally straightforward to use. The only point worth remembering is that cardinal numbers behave like post-determiners, which means they come after a central determiner: "the three cats," not "three the cats."

4. The order of determiners

When more than one determiner appears before a noun, they must follow a specific order. Grammarians divide determiners into three positions: pre-determiners, central determiners, and post-determiners.

| Position | What goes here | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-determiner | Multipliers, fractions, "all," "both," "half" | all, both, half, double, twice |

| Central determiner | Articles, demonstratives, possessives | the, a, this, my, your, which |

| Post-determiner | Numbers, quantifiers like "many," "few," ordinals | three, first, many, several, next, last |

The pattern is: pre-determiner + central determiner + post-determiner + (adjective) + noun. For example, "All my three older brothers live abroad." Here, "all" is the pre-determiner, "my" is the central determiner, and "three" is the post-determiner.

The most important rule is that you can only have one central determiner. You cannot say "the my house" or "this a problem." This is where many learners make errors, especially those whose first language allows stacking articles and possessives (as in Italian or Greek).

5. Determiners vs. adjectives

For a long time, grammar books classified words like "my," "this," and "some" as adjectives. You might still see terms like "possessive adjective" or "demonstrative adjective" in older textbooks. Modern grammar treats determiners as a separate word class, and there are good reasons for the distinction.

Here are the main differences.

- Adjectives describe qualities (big, red, beautiful), while determiners specify identity, quantity, or possession.

- Adjectives can be graded ("bigger," "biggest"), but you cannot say "more the" or "most my."

- Adjectives can follow a linking verb ("The cat is black"). However, it is wrong to say "The cat is the" or "The cat is my" without a noun following.

- You can stack several adjectives before a noun ("a big, old, red house"), but it is wrong to stack two central determiners ("the my house").

Adjectives sit between the determiner and the noun. The order is always determiner + adjective + noun, never "adjective + determiner + noun." You say "a funny film," not "funny a film."

6. Determiners vs. pronouns

Several words can be either a determiner or a pronoun, depending on context. The difference is whether or not a noun follows.

| As a determiner (before a noun) | As a pronoun (replacing a noun) |

|---|---|

| This cake is delicious. | This is delicious. |

| I want some water. | I want some. |

| Each player scored a goal. | Each scored a goal. |

| Which bus goes to Oxford? | Which goes to Oxford? |

In the left column, the word works as a determiner because it appears directly before a noun. In the right column, the same word works as a pronoun because it stands alone, replacing the noun entirely. This dual function is a frequent source of confusion in grammar exercises, so keep an eye on what follows the word.

7. Noun types

Not every determiner works with every kind of noun. In English, nouns split into two broad categories (countable and uncountable), and this distinction governs which determiners you can use. Getting this wrong is one of the most common mistakes in written and spoken English.

7.1 Countable nouns

Countable nouns are things you can count: one chair, two chairs, three chairs. When a countable noun is singular, it almost always needs a determiner. You cannot say "I sat on chair"; you need "I sat on a chair" or "I sat on the chair." When a countable noun is plural, a determiner is optional. "Chairs are useful" works perfectly well on its own as a general statement.

Some quantifiers only work with countable nouns: many, few, a few, several, and a number of. Saying "many water" or "few information" is incorrect because "water" and "information" are uncountable.

7.2 Uncountable nouns

Uncountable nouns (also called mass nouns) represent things that cannot be counted individually: water, information, furniture, advice, luggage. You cannot use "a" or "an" with them directly. Saying "an advice" or "a furniture" is a grammar error. Instead, you use quantity expressions like "a piece of advice" or "an item of furniture."

The quantifiers that pair with uncountable nouns include much, little, a little, a bit of, and a great deal of. You can also use determiners that work with both types: "some water," "the furniture," "no information."

7.3 Noun types and usage patterns

| Determiner | Singular countable | Plural countable | Uncountable |

|---|---|---|---|

| a / an | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| the | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| this / that | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| these / those | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| my, your, his, etc. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| some / any | ✓ (in certain uses) | ✓ | ✓ |

| many | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| much | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| few / a few | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| little / a little | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| each / every | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| no | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| several | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| enough | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| all | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| both | ✗ | ✓ (exactly two) | ✗ |

8. Zero article

Sometimes, the correct choice is no determiner at all. This is called "zero article," in English grammar. and it can confuse students because it feels counterintuitive; after being told that nouns need determiners, suddenly you are told some do not.

You leave out the determiner in the following cases:

- Plural countable nouns used in a general sense. "Dogs are loyal animals." (Talking about dogs in general, not specific dogs.)

- Uncountable nouns used in a general sense. "Water is essential for life." (Talking about water in general.)

- Proper nouns (most of the time). "London is a busy city." You would not say "The London is a busy city." (There are exceptions with certain proper nouns, particularly country names like "the United Kingdom" and geographical features like "the Thames.")

- Meals, sports, and academic subjects. "I had breakfast at seven." / "She plays tennis." / "He studies biology."

- Certain fixed expressions. "Go to bed," "at school," "by bus," "at work." These set phrases drop the article for historical and idiomatic reasons.

The difficult part is knowing when a noun is general (no article needed) and when it is specific (article required). Compare: "I like music" (general, no article) vs. "I like the music at this café" (specific, article needed). Context is everything.

9. Common mistakes

After teaching English for years and reviewing learner writing from dozens of language backgrounds, I have noticed the same errors appear many times. Here are the ones you should watch out for.

9.1 Dropping the determiner altogether

This is the most frequent mistake among learners whose first language has no articles (or uses them very differently). In English, a singular countable noun cannot stand alone as a subject or object. "I bought car" needs to be "I bought a car." "Cat is on the table" needs to be "The cat is on the table."

9.2 Stacking central determiners

You cannot put two central determiners together. "The my friend" is wrong; it should be "my friend." "This a problem" is wrong; it should be "this problem" or "a problem." Only pre-determiners (like "all," "both," "half") can appear before a central determiner: "all the students," "both my parents."

8.3 Mixing up countable and uncountable determiners

Using "many" with an uncountable noun ("many information") or "much" with a countable noun ("much problems") is a reliable way to lose marks in an exam. The fix is to learn the countability of common nouns. When in doubt, check a learner's dictionary; it will tell you whether a noun is countable [C] or uncountable [U].

9.4 Confusing "few" with "a few" and "little" with "a little"

"Few" and "little" (without the article) carry a negative meaning: hardly any. "A few" and "a little" carry a positive meaning: some, and that is enough. Compare: "He has few friends" (he is quite lonely) vs. "He has a few friends" (he has some friends, and that is fine). The same distinction applies to "little money" (almost none) vs. "a little money" (some, enough to get by).

9.5 Misusing "some" and "any"

The basic pattern is: some in positive sentences, any in negatives and most questions. "I have some questions" is correct. "I don't have any questions" is correct. "Do you have any questions?" is correct. Saying "Do you have some questions?" is not wrong in all cases (it can imply you expect the answer to be "yes"), but for most learners, sticking to the basic rule avoids errors.

9.6 Spelling "its" as "it's"

Even native speakers also spell these wrong. Its (no apostrophe) is the possessive determiner (e.g., The company changed its logo). It's (with an apostrophe) is a contraction of "it is" or "it has": "It's raining." If you can replace the word with "it is," use the apostrophe. If not, leave it out.

10. Usage in sentences

To tie everything together, let me show you how determiners function within the structure of a noun phrase. Every noun phrase in English follows this pattern:

(pre-determiner) + (central determiner) + (post-determiner) + (adjective/s) + noun

Here are a few examples broken down:

| Pre-det. | Central det. | Post-det. | Adjective(s) | Noun |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the | old | house | ||

| all | my | friends | ||

| a | tall, young | man | ||

| both | these | two | small | boxes |

| half | the | remaining | cake | |

| which | three | books |

Seeing the structure laid out like this makes it easier to spot when something is out of order. If you ever write a noun phrase that feels wrong, check whether you have accidentally put two words in the same slot, or placed a post-determiner before a central one.

11. Complete list of determiners in English

Here is a reference list of the most common determiners, grouped by type. This is not exhaustive (numbers, for instance, are infinite), but it covers every determiner you are likely to encounter in everyday English.

| Type | Determiners |

|---|---|

| Articles | a, an, the |

| Demonstratives | this, that, these, those |

| Possessives | my, your, his, her, its, our, their, whose |

| Quantifiers | some, any, no, many, much, few, a few, little, a little, several, enough, plenty of, a lot of, lots of, most, all, both, half |

| Distributives | each, every, either, neither |

| Interrogatives | which, what, whose |

| Numbers | one, two, three… ; first, second, third… |

| Pre-determiners | all, both, half, double, twice, three times, etc. |

| Difference | other, another |

Keep in mind that some of these words (such as "all," "both," and "some") can function as determiners, pronouns, or even adverbs, depending on how they are used in a sentence. The label "determiner" applies only when the word appears before a noun.

12. Summary

Determiners in English are a small set of words that do a large amount of work. They tell your listener which noun you mean, how many there are, and who owns them. The main types are articles, demonstratives, possessive determiners, quantifiers, distributives, interrogative determiners, and numbers.

Keep in mind that every singular countable noun needs a determiner, and only one central determiner is allowed per noun phrase. Beyond that, the key to improvement is learning which determiners pair with countable nouns, which pair with uncountable nouns, and which work with both.