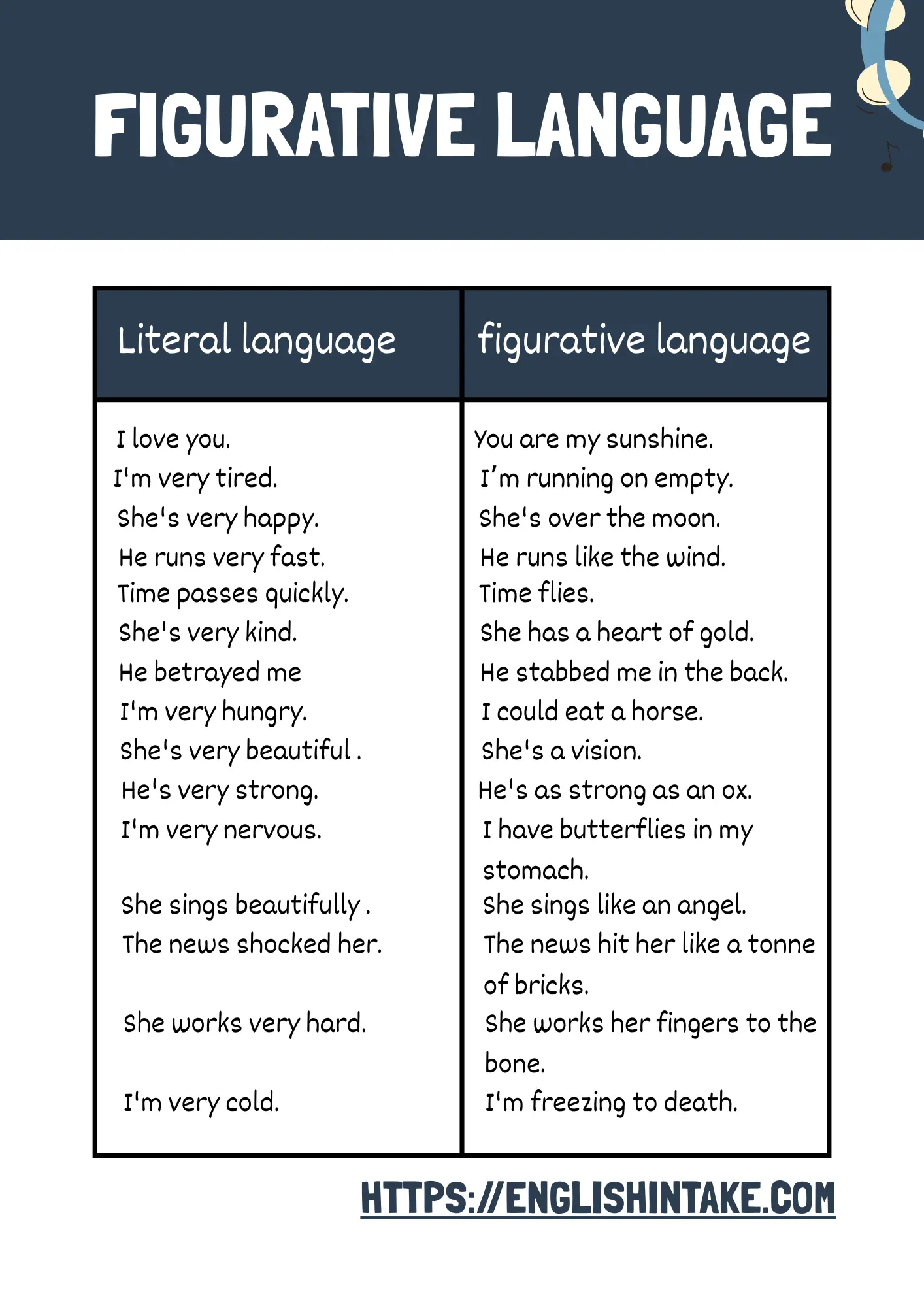

If you're wondering why English doesn't always mean what it says, it's because ordinary words often fail to capture how something truly feels. Telling someone "I love you very much" is accurate, but saying "you are my sunshine" conveys warmth, comfort, dependence, and joy in a single image. Literal language describes; figurative language makes you feel.

1. What is figurative language?

Figurative language is a way of using words that goes beyond their ordinary, dictionary meanings. Instead of saying exactly what you mean, you express ideas through comparisons, exaggerations, personification, symbolism, irony, understatement, sound effects (like alliteration), wordplay, etc. By doing so, you paint pictures in the listener’s mind.

When your friend says "I'm so hungry I could eat a horse," they're not literally planning to eat an entire horse. They're using figurative language to emphasise just how hungry they feel. This distinction between what words say and what they actually mean is at the heart of figurative expression.

Native English speakers and writers use figurative language constantly in everyday conversation, in films, in songs, and in written texts. Understanding these common literary devices is essential because taking words literally can lead to confusion or misunderstanding.

2. Why figurative language matters for English learners

Mastering figurative language transforms your English from textbook correct to naturally fluent. When you understand these expressions, you can follow conversations more easily, appreciate English literature and media, and express yourself in ways that resonate with native speakers.

Figurative language also carries cultural meaning. Many expressions reflect British or American history, customs, and values. Learning them gives you insight into how English speakers think and communicate; it connects you to the culture behind the language.

Moreover, figurative expressions appear everywhere: in job interviews, academic lectures, news reports, and casual chats with friends. Without this knowledge, you might miss important nuances or feel left out of conversations. The good news is that once you understand how figurative language works, recognising and using it becomes much easier.

3. Literal versus figurative meaning

Literal language means exactly what the words say. If someone tells you "the cat is on the mat," you can picture a cat physically sitting on a mat. There's no hidden meaning; the words describe reality directly.

Figurative language, by contrast, requires you to look beyond the surface. When someone says "let the cat out of the bag," they're not referring to an actual cat. They mean revealing a secret. The phrase works through association rather than direct description.

This difference often confuses learners initially. The key is to notice when a literal interpretation doesn't make logical sense. If "raining cats and dogs" were literal, you'd see animals falling from the sky. Since that's impossible, you know the expression must mean something else (in this case, heavy rain).

3.1 How to recognise figurative language

Context is your best friend when identifying figurative expressions. Ask yourself whether the literal meaning makes sense in the situation. If someone describes their boss as "a real dragon," consider whether a mythical fire-breathing creature could actually be someone's manager. Clearly not; the speaker means their boss is fierce or intimidating.

Certain signal words also help identify specific types of figurative language. Words like "as" and "like" often introduce similes. Extreme exaggerations ("I've told you a million times") signal hyperbole. With practice, you'll learn to spot these patterns automatically.

4. Similes: comparing with "like" or "as"

A simile compares two different things using the words "like" or "as." This comparison highlights a shared quality between them, creating a vivid image in the listener's mind.

Consider the simile "her smile was as bright as the sun." The speaker isn't saying the person's smile literally produces solar radiation. Instead, they're emphasising how radiant and warm her smile appeared. The sun, with its brightness and warmth, helps the listener visualise and feel the smile's impact.

4.1 Examples in everyday English

English contains many similes that appear regularly in conversation. "As busy as a bee" describes someone working hard and constantly moving. "Sleep like a log" means sleeping deeply without waking. "As cool as a cucumber" describes someone remaining calm under pressure.

Other frequently used similes include "as clear as crystal" (very easy to understand), "like a fish out of water" (uncomfortable or out of place), and "as light as a feather" (weighing very little). These expressions feel natural to native speakers because they've heard them countless times.

4.2 Creating your own similes

Once you understand similes, you can create your own. Think about what quality you want to emphasise, then find something that strongly represents that quality. If you want to describe someone who runs fast, you might say they run "like the wind" or are "as quick as lightning."

Avoid clichés when possible. While standard similes help you communicate clearly, fresh comparisons make your language more engaging. A well-chosen original simile can be more memorable than a familiar expression.

5. Metaphors: saying one thing is another

Metaphors compare two things directly by stating that one thing is another, without using "like" or "as." When Shakespeare wrote that "all the world's a stage," he wasn't saying the planet is literally a wooden platform with curtains. He meant that life resembles a theatrical performance where people play different roles.

Metaphors create powerful images because they collapse the distance between two ideas. Instead of suggesting similarity (as similes do), metaphors declare identity. This makes them more forceful and immediate.

5.1 Different types of metaphors

Descriptive metaphors compare concrete things: "the fog crept in on cat feet" (from Carl Sandburg's poem) pictures fog moving silently like a cat. Abstract metaphors explain ideas through concrete images: "time is money" helps us understand time as something valuable that can be spent or wasted.

Embedded metaphors use verbs or nouns figuratively without explicit comparison: "she devoured the book" doesn't mean she ate pages, but that she read eagerly. These metaphors blend so naturally into language that we often don't notice them.

5.2 The difference between metaphors and similes

Similes say something is like something else; metaphors say something is something else. "Her eyes were like stars" (simile) becomes "Her eyes were stars" (metaphor). Both express that her eyes were bright and captivating, but the metaphor feels more direct and dramatic.

Neither form is better than the other. Similes work well when you want to draw a clear comparison while acknowledging the difference between the two things. Metaphors work well when you want to merge two ideas completely for stronger emotional impact.

6. Idioms: expressions with hidden meanings

Idioms are fixed phrases whose meanings cannot be understood from their individual words. If someone tells you to "break a leg" before a performance, they're wishing you good luck, not hoping you'll injure yourself. There's nothing in the words "break," "a," or "leg" that suggests good fortune; you simply have to learn what the phrase means.

This is precisely what makes idioms challenging for English learners. Unlike similes and metaphors, where you can often guess the meaning from the comparison, idioms require prior knowledge. You must learn them as complete units, like vocabulary items.

6.1 Common British idioms

British English contains many distinctive idioms. "Bob's your uncle" (and you're done; it's that simple) puzzles learners who don't know anyone named Bob. "Bits and bobs" (various small items) uses rhyming words for no logical reason. "Chuffed to bits" means extremely pleased, though neither "chuffed" nor "bits" suggests happiness on its own.

Other everyday British idioms include "taking the mickey" (mocking someone), "donkey's years" (a very long time), and "having a butcher's" (taking a look, from Cockney rhyming slang where "butcher's hook" rhymes with "look").

6.2 Strategies for learning idioms

Learn idioms in context rather than memorising lists. When you encounter one in a film, book, or conversation, note the situation where it appeared. This helps you remember both the meaning and appropriate usage.

Group idioms by theme or topic. Weather idioms ("under the weather," "raining cats and dogs," "a storm in a teacup"), body part idioms ("keep your chin up," "cold feet," "all ears"), and colour idioms ("feeling blue," "green with envy," "seeing red") form memorable clusters.

Try explaining idioms in your own language. Many languages have similar expressions, though the images differ. Where English says "raining cats and dogs," other languages might describe raining buckets, ropes, or even old women. Finding these parallels deepens understanding.

7. Hyperbole: exaggeration for effect

Hyperbole uses extreme exaggeration to emphasise a point. No one expects you to take hyperbolic statements literally; their power lies in their obvious impossibility. "I've been waiting forever" doesn't mean eternal waiting (which would be impossible), but rather that the wait felt unreasonably long.

Hyperbole adds drama, humour, and emotional intensity to speech. It helps speakers express feelings more vividly than plain statements would allow.

7.1 Examples of hyperbole in daily conversation

You'll hear hyperbole constantly in everyday English. "I'm dying of embarrassment" (feeling extremely embarrassed), "this bag weighs a tonne" (the bag is very heavy), "I could sleep for a week" (I'm extremely tired). None of these statements describes reality, but each conveys emotion effectively.

Other common hyperboles include "I've told you a thousand times" (repeatedly), "she's the best person in the entire world" (I like her very much), and "my feet are killing me" (my feet hurt badly).

7.2 Using hyperbole appropriately

Hyperbole works best in informal situations where emotional expression is welcome. Casual conversations, friendly emails, and creative writing all accommodate exaggeration well. Formal contexts like academic papers or business reports generally require more precise language.

Be aware that cultural norms affect hyperbole usage. British English often favours understatement (saying less than you mean), while American English tends toward more direct exaggeration. Adjusting your style to your audience improves communication.

8. Personification: giving human qualities to non-human things

Personification attributes human characteristics, actions, or emotions to animals, objects, or abstract concepts. When we say "the wind howled through the trees," we know wind doesn't literally howl like a wolf. However, this description helps listeners imagine the sound more vividly than "the wind made a loud noise."

There are many examples of personification in literature because it makes descriptions more relatable by connecting non-human things to human experience. We understand emotions and actions because we experience them ourselves; applying them to other things helps us grasp their nature.

8.1 Recognising personification in English

Look for verbs typically associated with human action applied to non-human subjects. "The sun smiled down" (suns don't have mouths), "the alarm clock screamed at me" (clocks don't have voices), "the flowers danced in the breeze" (plants don't dance). Each example applies human behaviour to something that cannot literally perform that action.

Personification also appears when objects are described as having feelings. "The old house looked sad and forgotten" gives the building emotional states it cannot actually possess. This technique makes settings more atmospheric and memorable.

8.2 Personification versus apostrophe

Speaking to an object ("Come on, computer, work properly!") is called apostrophe, not personification. Personification requires the non-human thing to perform a human action or display a human quality. Addressing something that cannot respond is different from describing it as if it had human attributes.

9. Onomatopoeia: words that sound like sounds

Onomatopoeia refers to words that imitate natural sounds. "Buzz," "hiss," "splash," "bang," and "whisper" all sound somewhat like what they describe. This connection between sound and meaning makes onomatopoeic words particularly vivid and sensory.

English contains numerous onomatopoeic words for animal sounds (meow, woof, moo, quack), mechanical sounds (beep, click, clang, whirr), and natural sounds (splash, rustle, crack, drip). These words add life to descriptions by helping readers or listeners "hear" the scene.

9.1 Onomatopoeia varies across languages

Interestingly, onomatopoeia differs between languages even when describing identical sounds. English dogs say "woof," Japanese dogs say "wan-wan," and Korean dogs say "meong-meong." A French cockerel cries "cocorico" while an English one says "cock-a-doodle-doo."

These differences reflect how each language's sound system shapes perception. Learning English onomatopoeia helps you describe sounds in ways native speakers recognise and expect.

10. Alliteration: repeated initial sounds

Alliteration repeats the same consonant sound at the beginning of closely positioned words. "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers" repeats the "p" sound, creating a memorable, rhythmic phrase. Tongue twisters often use alliteration to create pronunciation challenges.

Alliteration appears frequently in brand names (Coca-Cola, PayPal, Dunkin' Donuts), newspaper headlines ("Brexit Britain Battles Budget Blues"), and poetry. The repeated sounds create cohesion and catch attention.

10.1 Why alliteration makes language memorable

Our brains process patterns more easily than random sequences. When sounds repeat, they create a rhythmic quality that aids memory. This explains why proverbs, advertising slogans, and memorable phrases often use alliteration.

Alliteration also adds musicality to language. Even in prose, strategic sound repetition makes sentences more pleasing to hear and easier to remember. Skilled writers use this technique subtly to enhance their work.

11. Other types of figurative language

11.1 Understatement

Understatement deliberately presents something as less significant than it actually is. If someone emerges from a terrible rainstorm and says "it's a bit damp out there," they're using understatement for comic effect. The British are particularly known for this technique, often describing serious situations with mild language.

Understatement works by creating contrast between words and reality. The listener recognises the gap and appreciates the speaker's restraint or irony.

11.2 Oxymoron

An oxymoron combines contradictory terms to create a meaningful expression. "Deafening silence," "bittersweet," "living dead," and "jumbo shrimp" all pair opposites. These combinations force us to consider how apparent contradictions can coexist.

Oxymorons often capture complex experiences that single words cannot express. "Bittersweet" perfectly describes moments that are simultaneously happy and sad, a feeling that neither "happy" nor "sad" alone would convey.

11.3 Irony

Irony involves saying the opposite of what you mean, or situations where outcomes contradict expectations. If someone ruins your work and you say "oh, that's just perfect," your tone makes clear you mean the opposite. Situational irony occurs when a fire station burns down or a swimming instructor drowns.

Understanding irony requires attention to context and tone. The words alone don't reveal ironic intent; you must recognise the mismatch between what's said and what's meant or expected.

11.4 Synecdoche and metonymy

Synecdoche uses a part to represent the whole, or vice versa. "All hands on deck" uses "hands" to mean workers. "New wheels" uses "wheels" to mean an entire car. The part stands for the complete thing.

Metonymy substitutes something closely associated with something else. "The Crown" represents the monarchy. "Hollywood" stands for the American film industry. "The pen is mightier than the sword" uses "pen" for writing/ideas and "sword" for military force.

12. Figurative language in songs and films

Popular music overflows with figurative language. Katy Perry's "Firework" calls the listener a firework capable of bursting with colour (metaphor). Adele sings about "rolling in the deep" (metaphor for emotional turmoil). Song lyrics use figurative language to compress complex emotions into memorable phrases.

Films similarly rely on figurative expressions in dialogue. Characters might say they're "in hot water" (in trouble), someone "stabbed them in the back" (betrayed them), or a situation is "do or die" (critical). Watching English-language media attentively helps you absorb these expressions in context.

12.1 Learning figurative language from lyrics

Song lyrics offer excellent figurative language practice because they combine emotional content with repetition. You'll likely hear your favourite songs multiple times, reinforcing the expressions used. Try identifying which type of figurative language each lyric contains.

Be aware that songs sometimes bend grammatical rules for rhythm or rhyme. The figurative expressions remain authentic, but other language features might be non-standard.

13. Common mistakes learners make with figurative language

13.1 Taking expressions literally

The most common mistake is interpreting figurative language as literal truth. When someone says "I nearly died laughing," they didn't actually approach death. When food is described as "to die for," no one expects fatalities. Learning to recognise figurative intent prevents embarrassing misunderstandings.

13.2 Mixing idioms incorrectly

Idioms are fixed expressions; changing their words creates confusion. "We'll cross that bridge when we come to it" becomes nonsense if you say "we'll cross that road when we reach it." Similarly, mixing two idioms ("we'll burn that bridge when we come to it") creates unintended meanings.

13.3 Using expressions in wrong contexts

Some figurative expressions suit informal speech but feel odd in formal writing. Others carry cultural connotations that may not translate across different English-speaking regions. "Chuffed" sounds distinctly British; "stoked" sounds American. Matching expressions to context improves fluency.

14. Practical tips for mastering figurative language

14.1 Keep a figurative language journal

When you encounter new expressions, write them down with their meanings, the context where you found them, and example sentences. Reviewing this journal regularly builds your passive understanding into active usage.

14.2 Immerse yourself in native content

Watch British films and television with subtitles initially. Listen to podcasts hosted by native speakers. Read novels, newspapers, and magazines. The more exposure you get, the more natural figurative language will feel.

14.3 Compare with your native language

Your first language almost certainly contains figurative expressions too. Exploring how your language handles metaphors, idioms, and exaggerations deepens your understanding of how figurative language works universally, while highlighting English-specific patterns.

14.4 Start using expressions yourself

Active use consolidates learning far better than passive recognition. Try incorporating one new figurative expression into your English each day. Make mistakes, get feedback, and gradually build confidence.

15. Figurative language and cultural understanding

Figurative expressions often encode cultural values and historical experiences. British idioms frequently reference weather (unsurprisingly, given the climate) and social class. American idioms draw heavily on baseball, frontier history, and business terminology.

Understanding these cultural roots enriches your language learning. When you learn that "the proof of the pudding is in the eating" comes from medieval British cooking traditions, the expression becomes more memorable and meaningful.

Figurative language also reflects how a culture thinks about abstract concepts. English treats time as money (we "spend," "waste," and "save" time). Other languages might conceptualise time differently. These metaphors shape thought as much as they express it.

16. Bringing it all together

Figurative language transforms English from a simple communication tool into a rich, expressive medium. Similes and metaphors create vivid comparisons. Idioms carry cultural wisdom in compact phrases. Hyperbole, personification, and alliteration add colour and emphasis to everyday speech.

As an English learner, you don't need to master every expression immediately. Focus first on recognising figurative language when you encounter it, then gradually build your repertoire through exposure and practice. Over time, you'll find yourself understanding more and expressing yourself more naturally.

The ability to use figurative language appropriately marks a significant milestone in English fluency. It shows you understand not just words but the creative, cultural, and emotional dimensions of the language. Keep learning, keep practising, and soon figurative language will feel like second nature.