1. What is foreshadowing?

Foreshadowing is a narrative technique where writers plant clues about events that will unfold later in the story. These subtle suggestions create anticipation. The idea is to keep the readers engaged without realising that they are being guided towards a particular outcome.

Think of foreshadowing as a promise from the writer to the reader. A seemingly innocent detail mentioned early in a story often carries weight that only becomes clear in hindsight. This technique appears across all storytelling mediums, from classic literature to modern films and television series.

2. Why writers use foreshadowing

Writers use foreshadowing primarily to build suspense throughout their narratives. By dropping hints about what lies ahead, they keep readers turning pages, eager to discover how events will unfold. This technique transforms passive reading into an active experience where audiences piece together clues.

Beyond suspense, foreshadowing creates narrative cohesion. When a major plot twist arrives, readers can look back and recognise the groundwork laid earlier. This makes endings feel satisfying rather than arbitrary. Foreshadowing takes advantage of the difference between plot (the linear order of events) and narrative (how those events are told).

It also adds depth to subsequent readings or viewings. Knowing the ending allows audiences to appreciate the craftsmanship behind each planted clue. Many beloved stories reward this kind of revisiting with layers of meaning that only become apparent the second time through.

3. Types of foreshadowing

3.1 Direct foreshadowing

Direct foreshadowing occurs when an author explicitly states or strongly implies something that will happen later. This approach leaves little to interpretation and serves as a clear signal to pay attention. Shakespeare's prologues oftenuse this technique.

Consider how some novels open with statements like "that was the summer everything changed" or "little did I know this decision would haunt me." These announcements create immediate tension because readers know something significant is coming.

3.2 Indirect foreshadowing

Indirect foreshadowing uses symbols, imagery, or seemingly minor details to hint at future events. This subtler approach often goes unnoticed during a first reading. Weather, recurring motifs, and character mannerisms can be used for indirect foreshadowing.

A story that repeatedly mentions storm clouds gathering, for example, might be preparing readers for conflict ahead. Similarly, a character who nervously checks locked doors could be signalling future danger.

3.3 Chekhov's gun

Anton Chekhov, the renowned Russian playwright, articulated a principle that has become fundamental to storytelling: if a loaded rifle hangs on the wall in the first act, it must fire by the final act. This principle, known as Chekhov's gun, suggests that every element in a story should serve a purpose.

Chekhov's gun differs slightly from general foreshadowing in its emphasis on necessity. Whilst foreshadowing hints at future events, Chekhov's gun insists that introduced elements must eventually become significant. James Bond films exemplify this beautifully, with gadgets presented early always proving crucial later.

3.4 Red herrings

Red herrings represent a deliberate subversion of foreshadowing expectations. Writers introduce elements that appear significant but ultimately prove misleading, diverting attention from the true direction of the plot. Mystery and detective fiction rely heavily on this technique to maintain suspense.

The suspicious butler who seems guilty but turns out innocent is a classic red herring. These false trails keep audiences guessing and make genuine reveals more surprising. However, even red herrings should have some connection to the story to avoid frustrating readers.

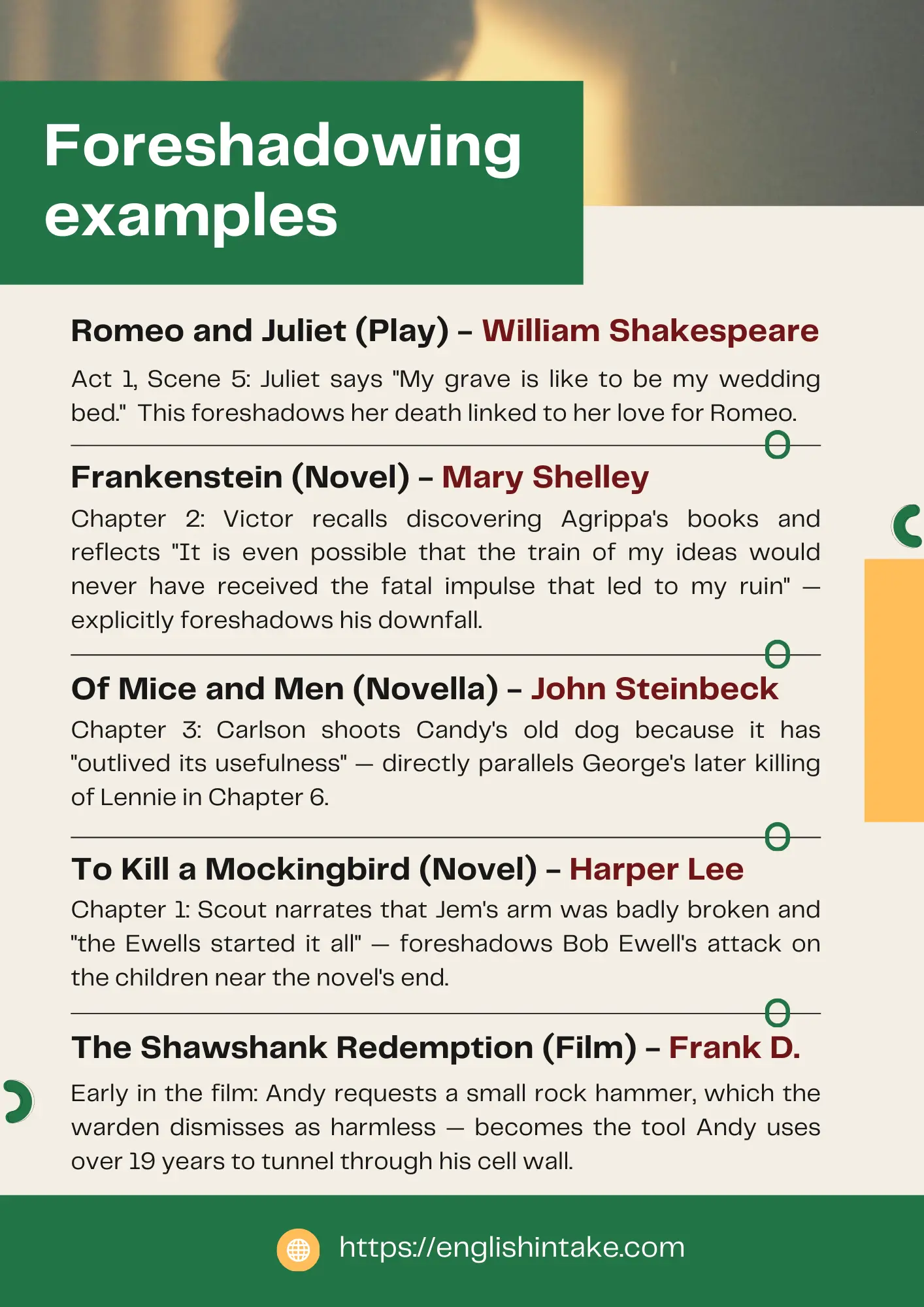

Find below many foreshadowing examples used in plays, novels, novellas, and films to help you write short sentences that hint at what will happen later in the story.

4. Foreshadowing examples in literature

4.1 Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

The prologue in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet explicitly announces that the "star-crossed lovers take their life," eliminating any suspense about the outcome whilst heightening tension about how this tragedy will unfold.

Throughout the play, both protagonists repeatedly reference death in ways that prove prophetic. Romeo declares he would rather die than live without Juliet's love, whilst Juliet states "my grave is like to be my wedding bed." These statements feel romantic in context but carry darker significance in retrospect.

Friar Laurence's words "these violent delights have violent ends" prove tragically accurate as the lovers' intense passion leads to their mutual destruction. Even their final vision of each other appearing pale foreshadows the death that awaits.

4.2 Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein use both explicit and subtle foreshadowing through its narrator, Victor Frankenstein. Because Victor narrates from years after the events, he possesses knowledge that allows him to hint at coming disasters. He describes his early interest in occult philosophy as receiving "the fatal impulse that led to my ruin."

A more subtle example occurs when young Victor witnesses lightning destroy an oak tree. At the time, this scene merely demonstrates nature's power. Later, when Victor uses electricity to animate his creature, readers recognise this earlier moment as clever groundwork for the central plot.

4.3 Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Early in the story, an old dog that has outlived its usefulness is put down by a farmhand. This seemingly minor episode directly parallels Lennie's fate at the story's conclusion.

George's killing of the dog establishes a pattern that readers later recognise. When George must make an impossible decision about Lennie, the parallel becomes heartbreakingly clear. The earlier scene prepared readers emotionally whilst also demonstrating George's capacity for difficult mercy.

4.4 A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway opens A Farewell to Arms with a line: "The leaves fell early that year." This simple observation about nature hints at the premature deaths that will punctuate the narrative, establishing a tone of inevitable loss.

Throughout the novel, Catherine expresses an unexplained fear of rain. This recurring anxiety gains devastating meaning at the novel's end when she dies during childbirth and the narrator walks away alone in the rain. Hemingway transforms weather into a symbol of death throughout, making rain an ominous presence.

4.5 To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

In the opening pages, Scout mentions that Jem broke his arm badly when he was nearly thirteen, then adds that the Ewells "started it all." This creates immediate mystery whilst pointing towards the climactic confrontation.

Atticus Finch also unknowingly foreshadows his own actions when explaining courage to his children. He describes it as knowing "you're licked before you begin, but you begin anyway and see it through no matter what." This perfectly describes his approach to Tom Robinson's doomed court case.

5. Foreshadowing examples in film

5.1 The Shawshank Redemption

Andy Dufresne's request for a small rock hammer seems innocent enough. The warden dismisses it as harmless, and audiences might forget about it entirely. Yet this tiny tool becomes central to Andy's escape, representing years of patient work towards freedom.

The film also plants clues through Andy's discussions of Zihuatanejo, the Mexican coastal town where he dreams of living. What seems like wishful thinking becomes the destination for both Andy and Red, rewarding attentive viewers who noticed this recurring detail.

5.2 The Sixth Sense

M. Night Shyamalan's film rewards repeat viewings with extensive foreshadowing of its famous twist. Malcolm Crowe's inability to open doors, his wife's apparent coldness, and his isolation in social situations all hint at his true condition throughout.

The film's careful construction means that knowing the ending transforms every scene. What initially appears as a troubled marriage becomes something far more poignant. This level of foreshadowing craftsmanship made the film a touchstone for twist endings.

5.3 The Harry Potter series

The philosopher's stone introduces Sirius Black merely as someone who lent Hagrid a flying motorcycle, a seemingly throwaway line that becomes crucial in the third instalment.

Professor Trelawney's predictions, often treated as jokes, prove eerily accurate. Her statement that "when thirteen dine together, the first to rise will be the first to die" comes true multiple times across the series. Harry and Ron's fake Divination homework even predicts the Triwizard Tournament tasks.

The vanishing cabinet that Harry notices in Borgin and Burkes during his second year becomes instrumental to Voldemort's plan four books later. Rowling planted seeds years in advance, creating a rich tapestry of interconnected details that rewarded devoted readers.

6. Identification

Developing an eye for foreshadowing enriches your reading experience considerably. Start by paying attention to recurring images, symbols, or motifs within a text. Authors rarely repeat details without purpose, so patterns often signal significance.

Notice when characters make statements about the future, whether predictions, fears, or offhand comments. Dialogue that seems unusually specific or emphatic often carries foreshadowing weight. Similarly, dreams, premonitions, and prophecies within stories frequently prove accurate.

Consider the setting and atmosphere carefully. Dark, stormy weather or unsettling descriptions often precede conflict or tragedy. Objects that receive unusual attention from the narrator may prove important later. If a detail seems oddly specific or out of place, it might well be foreshadowing.

7. Foreshadowing versus flash-forward

Although both techniques relate to future events, foreshadowing and flash-forwards function quite differently. Foreshadowing hints at what will happen whilst remaining firmly in the present narrative moment. It suggests without revealing, creating anticipation rather than certainty.

Flash-forwards, by contrast, actually transport the narrative to a future point in time. They show rather than hint, revealing events that will occur before returning to the present timeline. A Christmas Carol employs flash-forward when the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows Scrooge his own grave.

The distinction matters for understanding authorial intent. Foreshadowing asks readers to engage actively with clues and predictions. Flash-forwards provide direct knowledge whilst creating mystery about how characters reach that future point.

8. Correct usage in writing

Effective foreshadowing requires planning your story's ending before you begin. Knowing where you are heading allows you to plant appropriate clues throughout the narrative. Many successful authors write their endings first, then layer in hints during revision.

Balance subtlety with clarity. Foreshadowing that proves too obvious spoils surprises, whilst overly obscure hints frustrate readers. Aim for details that feel natural in their moment but gain significance in retrospect. Multiple readers or beta readers can help calibrate this balance.

Vary your techniques across a single work. Combine direct statements, symbolic imagery, dialogue, and character behaviour to create layered foreshadowing. This variety keeps readers engaged without becoming predictable. Remember that foreshadowing should enhance your story, not distract from it.