1. What are literary devices?

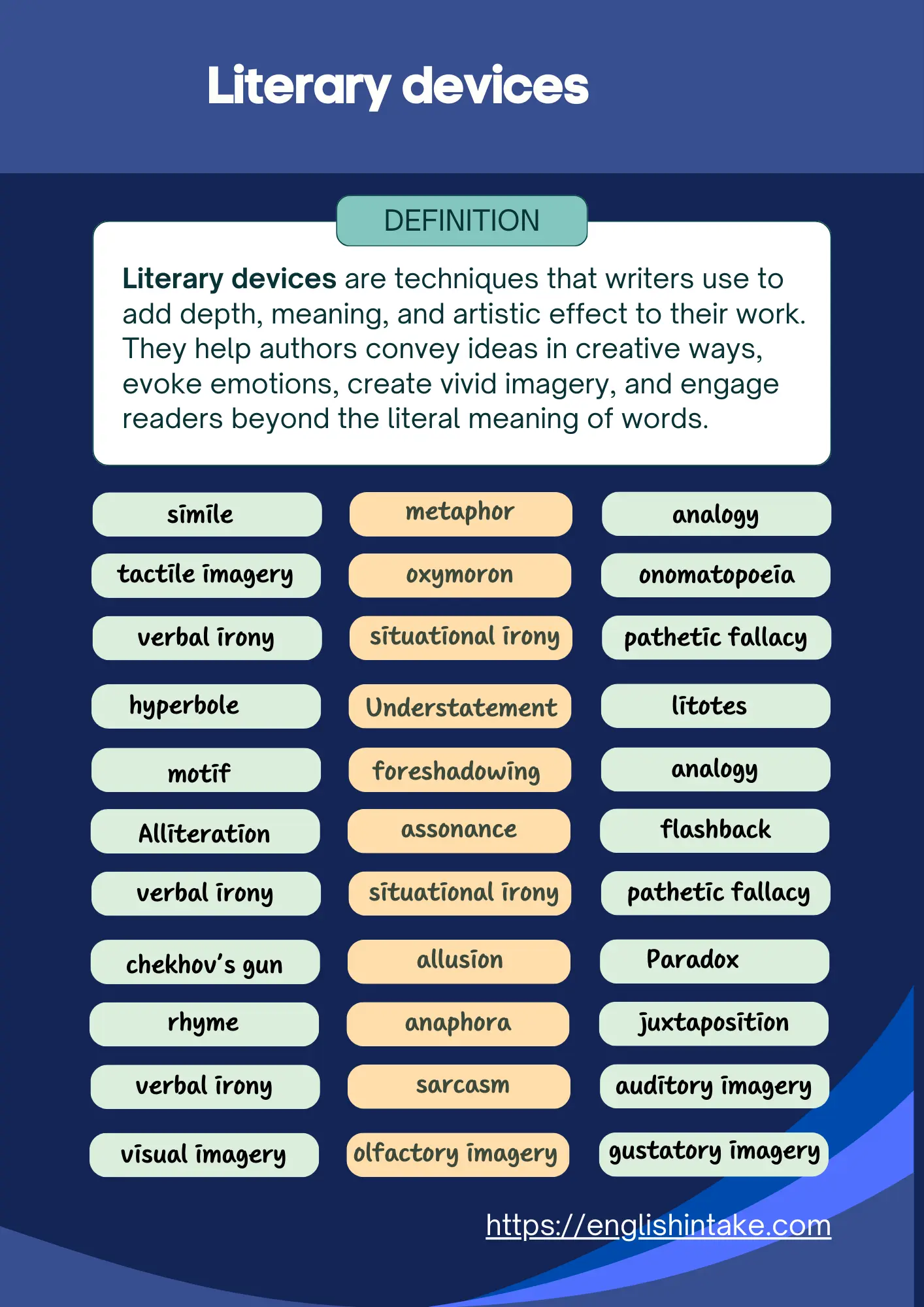

Literary devices are techniques that writers use to create meaning, evoke emotion, and engage readers beyond the literal level of words. They are the tools in a writer's toolkit that transform ordinary sentences into memorable prose and poetry.

When you read a sentence like "the wind whispered through the trees," you instinctively understand the wind is not actually whispering. The writer has used personification to create an image that feels alive. That is a literary device at work.

Understanding these devices serves two purposes: it helps you appreciate the craft behind great writing, and it gives you techniques to improve your own work.

1.1 Literary elements vs literary techniques

Many learners confuse literary elements with literary techniques, but they operate at different levels. Literary elements are the foundational building blocks that make up every story: plot, setting, character, theme, and point of view. Every narrative contains these components.

Literary techniques, on the other hand, are specific methods writers employ within sentences and paragraphs to achieve particular effects. Metaphors, similes, alliteration, and irony fall into this category. Think of elements as the skeleton of a story, whilst techniques are the muscles that give it movement and expression.

A third term you may encounter is figurative language, which refers specifically to expressions that convey meaning beyond their literal interpretation. Figurative language includes devices like metaphor, simile, personification, and hyperbole.

2. Comparison devices: simile, metaphor, and analogy

These three devices are among the most commonly used in English, yet they cause considerable confusion because all three involve comparing one thing to another. The difference lies in how the comparison is constructed and what purpose it serves.

2.1 Simile

A simile compares two unlike things using the words "like" or "as." This explicit comparison helps readers visualise abstract ideas through familiar images.

Consider Robert Burns's famous line: "My love is like a red, red rose." The poet does not claim his beloved is literally a flower. Instead, by using "like," he invites the reader to consider what qualities a rose and his love might share: beauty, fragrance, perhaps the fleeting nature of bloom.

The signal words "like" and "as" make similes easy to identify. When someone says "she swam like a fish" or "the exam was as hard as nails," they are using similes to paint quick, vivid pictures.

2.2 Metaphor

A metaphor makes a direct comparison without using "like" or "as." It states that one thing is another, creating a more immediate and forceful connection.

Shakespeare's famous line "All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players" does not suggest the world resembles a stage. It declares the world is a stage. This directness creates a stronger impact because it forces the reader to accept the comparison without the softening effect of "like."

Metaphors often work subconsciously in everyday speech. Phrases such as "time is money," "he has a heart of stone," and "life is a journey" are all metaphors we use without thinking. Each one shapes how we understand abstract concepts by connecting them to concrete experiences.

2.3 Analogy

An analogy is an extended comparison that explains an unfamiliar concept by relating it to something familiar. Unlike metaphors and similes, which often serve poetic or descriptive purposes, analogies primarily serve explanatory ones.

A teacher might explain how the human heart works by saying: "The heart is like a pump with four chambers. Just as a pump pushes water through pipes, the heart pushes blood through your veins and arteries." This analogy does not aim for poetic beauty; it aims for clarity.

The key distinction is purpose. Similes and metaphors create images and evoke emotions. Analogies clarify complex ideas by mapping them onto simpler, more familiar concepts. An analogy typically develops over several sentences and explains why the comparison matters, whereas similes and metaphors usually appear in single phrases.

2.4 Quick reference: telling them apart

When you encounter a comparison, ask yourself three questions. Does it use "like" or "as"? If yes, it is a simile. Does it directly state that one thing is another? Then it is a metaphor. Does it extend over several sentences to explain how two things are similar and why that similarity matters? That is an analogy.

Here is an example of all three describing the same concept. Simile: "Her mind worked like a computer, processing information rapidly." Metaphor: "Her mind was a supercomputer." Analogy: "Her mind functioned like a computer's processor. Just as a processor handles millions of calculations per second, her thoughts moved rapidly from problem to solution, filtering out irrelevant data and focusing only on what mattered."

3. Sound devices

Sound devices create rhythm, emphasis, and musicality in writing. They appeal to the ear and make text more memorable. Poets rely heavily on these techniques, but prose writers use them too.

3.1 Alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of consonant sounds at the beginning of words in close succession. The phrase "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers" is an extreme example. In more subtle forms, alliteration creates a pleasing rhythm: "the soft summer sun" or "dark and dangerous."

Writers use alliteration to draw attention to particular phrases, create a sense of cohesion, or establish a specific mood. Hard consonants like "k," "p," and "t" can create tension or aggression, whilst softer sounds like "s," "l," and "m" often suggest gentleness or calm.

3.2 Assonance

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds within words, regardless of the consonants around them. Unlike rhyme, the words do not need to end with the same sound; they simply share a vowel sound somewhere within.

Consider the phrase "the light of the fire." The long "i" sound in "light" and "fire" creates internal harmony. Edgar Allan Poe was a master of assonance; his line "And the silken sad uncertain rustling" uses the short "u" sound to create an uneasy, whispering effect.

3.3 Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia refers to words that imitate the sounds they describe. "Buzz," "hiss," "crash," "whisper," and "sizzle" are all examples. These words bring immediacy to writing because readers can almost hear what is being described.

Comic books famously use onomatopoeia: "POW!" "BANG!" "SPLASH!" In more literary contexts, the technique appears more subtly. A sentence like "the bacon sizzled in the pan while the coffee maker gurgled" uses sound words to make a kitchen scene come alive.

4. Irony and its types

Irony is one of the most frequently misunderstood literary concepts. At its core, irony involves a contrast between appearance and reality, between expectation and outcome, or between what is said and what is meant. There are three main types, each functioning differently.

4.1 Verbal irony

Verbal irony occurs when someone says the opposite of what they mean. If you step outside into a downpour and say, "What lovely weather we're having," you are using verbal irony.

Sarcasm is a form of verbal irony, but not all verbal irony is sarcasm. The difference lies in intent: sarcasm aims to mock or wound, whilst verbal irony can be playful, neutral, or even affectionate. When a parent says to a child covered in mud, "Well, aren't you a picture of elegance," that is verbal irony. Whether it is sarcastic depends on the tone and context.

4.2 Situational irony

Situational irony occurs when the outcome of a situation differs dramatically from what was expected. The classic example is O. Henry's short story "The Gift of the Magi," in which a wife sells her long hair to buy a watch chain for her husband, whilst the husband sells his watch to buy combs for her hair. Each sacrifices their treasure to honour the other's, yet their gifts become useless.

This type of irony often highlights the unpredictability of life. A fire station burning down, a pilot having a fear of heights, or a traffic jam preventing someone from reaching a job interview at a punctuality seminar: these scenarios all create situational irony.

4.3 Dramatic irony

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something that the characters do not. This creates tension, suspense, or poignancy as viewers watch characters act on incomplete information.

Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet provides the most famous example. When Romeo discovers Juliet's seemingly lifeless body and drinks poison, the audience knows she is merely drugged and will wake soon. This knowledge makes his death far more tragic than it would be if we, like Romeo, believed her truly dead.

Horror films frequently employ dramatic irony. When the audience sees a killer hiding in the wardrobe whilst the character enters the room unsuspecting, the tension arises from our knowledge of the danger they cannot see.

4.4 Irony vs coincidence

Many people misuse the word "ironic" to describe events that are merely unfortunate or coincidental. Rain on your wedding day is not ironic; it is simply bad luck. However, rain on your wedding day becomes ironic if you specifically chose the date because historical weather data showed it had never rained on that day in recorded history.

For true irony, there must be a meaningful contrast between expectation and reality, not just an unexpected event. A police officer getting a parking ticket is coincidental. A police officer who writes parking tickets for a living getting a parking ticket at the police station whilst attending a seminar on parking regulations is ironic.

5. Imagery and sensory language

Imagery refers to language that appeals to the senses. Strong imagery helps readers see, hear, smell, taste, and feel what is being described. Rather than telling readers what to think, imagery shows them and allows them to experience the text.

5.1 The five types of imagery

Visual imagery appeals to sight and is the most common type. "The crimson leaves carpeted the forest floor" creates a picture in the reader's mind.

Auditory imagery appeals to hearing. "The floorboards creaked with each step, and somewhere in the house, a clock ticked relentlessly" puts sounds in the reader's ear.

Olfactory imagery evokes smell. "The bakery exhaled warm clouds of cinnamon and yeast" captures a scent memory many readers will recognise.

Gustatory imagery relates to taste. "The lemon's sharp bite made her wince" lets readers experience a flavour.

Tactile imagery appeals to touch. "The woollen blanket scratched against her cheek" conveys physical sensation.

5.2 Using imagery effectively

Effective imagery is specific rather than general. "The flower smelled nice" tells readers almost nothing. "The jasmine released its cloying sweetness into the humid night air" creates an atmosphere.

The best imagery combines multiple senses. A description of a marketplace might include the shouting of vendors (auditory), the piles of spices in terracotta bowls (visual), the scent of roasting meat (olfactory), the sticky residue of overripe fruit underfoot (tactile), and the metallic tang of blood from the butcher's stall (gustatory). Such layered imagery creates immersive experiences.

6. Personification and related devices

Personification gives human qualities to non-human entities: objects, animals, or abstract concepts. When we say "the wind howled" or "opportunity knocked," we attribute human actions to things that cannot literally perform them.

6.1 How personification works

Personification makes the non-human relatable. Describing the sun as "smiling down" or fear as "creeping up your spine" helps readers connect emotionally with inanimate or abstract subjects.

Emily Dickinson personified death as a gentleman caller: "Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me." This personification transforms an abstract concept into a character, making mortality feel less terrifying and more like a polite visitor.

6.2 Pathetic fallacy

Pathetic fallacy is a specific type of personification in which nature reflects human emotions. When a character feels sad and it begins to rain, or when a joyful scene takes place under brilliant sunshine, the weather mirrors the emotional content of the narrative.

The term comes from John Ruskin, who coined it in the 19th century. "Pathetic" here relates to "pathos" (emotion), not to the modern sense of being pitiable. This technique appears throughout literature: storms accompany tragedies, spring blooms signal new beginnings, and harsh winters represent emotional coldness.

7. Hyperbole and understatement

These two devices sit at opposite ends of a spectrum. Hyperbole exaggerates for effect; understatement deliberately minimises.

7.1 Hyperbole

Hyperbole uses extreme exaggeration that no one expects to be taken literally. "I've told you a million times" and "I'm so hungry I could eat a horse" are everyday examples. The purpose is not to deceive but to emphasise.

In literature, hyperbole can create humour, stress importance, or convey emotional intensity. When a character says "I would die without you," readers understand this as an expression of deep attachment, not a literal prediction.

7.2 Understatement and litotes

Understatement presents something as less significant than it is. If someone wins the lottery and says, "Well, that's rather nice," they are using understatement. The technique often creates dry humour or emphasises by contrast.

Litotes is a specific form of understatement that uses double negatives to make a positive statement. Saying "she's not unintelligent" means she is intelligent but conveys this with deliberate restraint. "The test wasn't exactly easy" suggests it was difficult. Litotes often carries an ironic or understated quality that direct statements lack.

8. Symbolism and motif

Symbolism uses concrete objects, characters, or events to represent abstract ideas. A dove symbolises peace. A red rose symbolises love. A storm symbolises turmoil. Symbols work because cultures have built associations over time between certain images and certain meanings.

8.1 How symbolism works

Symbols can be universal or contextual. Some symbols carry the same meaning across many cultures: light typically represents good or knowledge, whilst darkness represents evil or ignorance. Other symbols gain meaning within a specific text. In F. Scott Fitzgerald's "The Great Gatsby," the green light at the end of Daisy's dock symbolises Gatsby's hopes and dreams; this meaning exists only within that novel's context.

Effective symbolism operates subtly. If a writer explicitly states "the broken mirror symbolised her shattered self-image," the symbol loses its power. Readers should feel the meaning rather than have it explained to them.

8.2 Motif

A motif is a recurring element (an image, phrase, situation, or idea) that develops or informs the major themes of a work. Whilst a symbol represents something once or occasionally, a motif appears repeatedly throughout a text.

In Shakespeare's Macbeth, blood appears as a motif. Lady Macbeth tries to wash imaginary blood from her hands; Macbeth sees blood on his dagger. Each appearance reinforces themes of guilt and the impossibility of escaping one's crimes. The repetition builds meaning.

9. Foreshadowing and flashback

These devices manipulate time and anticipation within narratives. Foreshadowing hints at what is to come; flashback reveals what has already occurred.

9.1 Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing plants clues early in a narrative that hint at later events. These clues create suspense, build anticipation, and make eventual revelations feel earned rather than arbitrary.

It can be subtle or direct. A character mentioning they cannot swim early in a story foreshadows a potential drowning scene later. A dark cloud on the horizon might foreshadow trouble ahead. The title of Thomas Hardy's novel "Death on the Nile" foreshadows what readers should expect.

Note that foreshadowing differs from Chekhov's gun, which states that if a gun appears in the first act, it must be fired by the third. Chekhov's principle concerns narrative efficiency; foreshadowing concerns creating anticipation.

9.2 Flashback

A flashback interrupts the present narrative to show events from the past. This technique provides backstory, reveals character motivation, or explains present circumstances.

Flashbacks must be handled carefully to avoid confusing readers. Writers typically signal a transition to the past through verb tense changes, visual cues, or explicit markers like "Ten years earlier..."

10. Allusion

An allusion is an indirect reference to a person, place, event, or work that the writer expects readers to recognise. Allusions allow writers to convey complex ideas quickly by drawing on shared cultural knowledge.

10.1 Types of allusion

Allusions can reference mythology (calling someone an "Achilles" to suggest they have a hidden weakness), religion (describing a place as "a garden of Eden"), literature (saying someone has "a Midas touch"), history (comparing a decision to "crossing the Rubicon"), or popular culture (calling someone "the Einstein of cooking").

Effective allusion requires that readers share the reference. An allusion to Hamlet's "to be or not to be" works because most English readers recognise it. An allusion to an obscure mediaeval text might work in academic writing but fail in popular fiction.

10.2 Allusion vs direct reference

Allusions are indirect and assume knowledge. If a writer says "she met her Waterloo," they expect readers to know about Napoleon's defeat. A direct reference would explain: "she faced defeat as Napoleon did at Waterloo." The allusion is more elegant but less accessible.

11. Paradox and oxymoron

Both devices involve contradiction, but they operate differently and create different effects.

11.1 Paradox

A paradox is a statement that appears to contradict itself but reveals a deeper truth upon reflection. Oscar Wilde was a master of paradox: "I can resist everything except temptation" seems contradictory but captures a genuine human experience.

"Less is more" appears illogical, yet it expresses a valid aesthetic principle. "The only constant is change" contains a logical contradiction that nonetheless describes reality accurately. Paradoxes invite readers to think beyond surface logic.

11.2 Oxymoron

An oxymoron combines two contradictory words in a single phrase. "Deafening silence," "living dead," "bittersweet," and "jumbo shrimp" are all oxymorons. The contradiction creates emphasis or captures complex experiences that single words cannot express.

Where paradox is a statement that seems false but is true, oxymoron is a phrase that combines opposites. "Act naturally" is an oxymoron (the words contradict), but "the more you know, the more you realise you don't know" is a paradox (the statement seems contradictory but reveals truth).

12. How to analyse literary devices (not just identify them)

Many students learn to spot literary devices but struggle to analyse them. Identifying a metaphor is the beginning, not the end, of literary analysis. The real question is always: what effect does this device create, and why did the writer choose it?

12.1 A framework for analysis

When you encounter a literary device, ask yourself four questions. What is the device? How does it work in this specific instance? What effect does it create for the reader? Why might the author have chosen this particular device at this point in the text?

Suppose you find the metaphor "time is a thief" in a poem about ageing. Do not simply write "the poet uses a metaphor." Instead, explain that by portraying time as a thief, the poet suggests time takes things from us without permission or warning, that its theft is sneaky and unpreventable, and that this metaphor reinforces the speaker's sense of loss and powerlessness against mortality.

12.2 Connecting devices to larger meaning

Literary devices serve the larger purposes of a text. They support themes, develop characters, establish tone, and guide reader responses. Always connect your analysis of individual devices to the work's broader meaning.

If a novel repeatedly uses storm imagery whenever the protagonist faces internal conflict, this pattern (a motif) reinforces the theme that inner turmoil manifests outwardly. The storms are not mere background; they externalise psychology and unify the narrative.

13. Using literary devices in your own writing

Reading about literary devices is useful, but applying them is where real learning happens. Here are principles for incorporating devices into your writing effectively.

13.1 Start with clarity

Before adding figurative language, ensure your literal meaning is clear. Literary devices should enhance communication, not obscure it. A confused metaphor is worse than a plain statement.

13.2 Avoid clichés

Expressions like "busy as a bee," "cold as ice," and "quiet as a mouse" were once fresh comparisons. Through overuse, they have lost their impact. When you find yourself reaching for a familiar phrase, push yourself to create something original.

13.3 Match device to purpose

Different devices serve different functions. Use metaphors when you want to create strong identification between two things. Use similes when you want to compare whilst maintaining distinction. Use analogies when you need to explain something complex. Use imagery when you want readers to experience a scene sensorily.

13.4 Practice restraint

Overusing literary devices draws attention to the writing rather than the message. A paragraph crammed with metaphors, alliteration, and hyperbole becomes exhausting. The most effective writing uses devices strategically, placing them where they create maximum impact.

14. Summary and further learning

Literary devices are not decorations; they are functional tools that help writers communicate more effectively. Understanding them deepens both your reading and writing abilities.

The devices covered in this guide represent the most commonly encountered in English literature and everyday communication. Comparison devices (simile, metaphor, analogy), sound devices (alliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia), irony (verbal, situational, dramatic), imagery, personification, hyperbole, understatement, symbolism, foreshadowing, flashback, allusion, paradox, and oxymoron: these form the core vocabulary of literary analysis.

Learning these devices is the first step. The next is recognising them in texts you read, and the step after that is using them consciously in your own writing. With practice, many of these techniques become intuitive, appearing naturally in your prose as you develop your voice as a writer.