Third person point of view places the narrator outside the story, telling it through an observer's eyes. Characters are referred to as he, she, or they rather than speaking for themselves as I.

1. What is third person point of view?

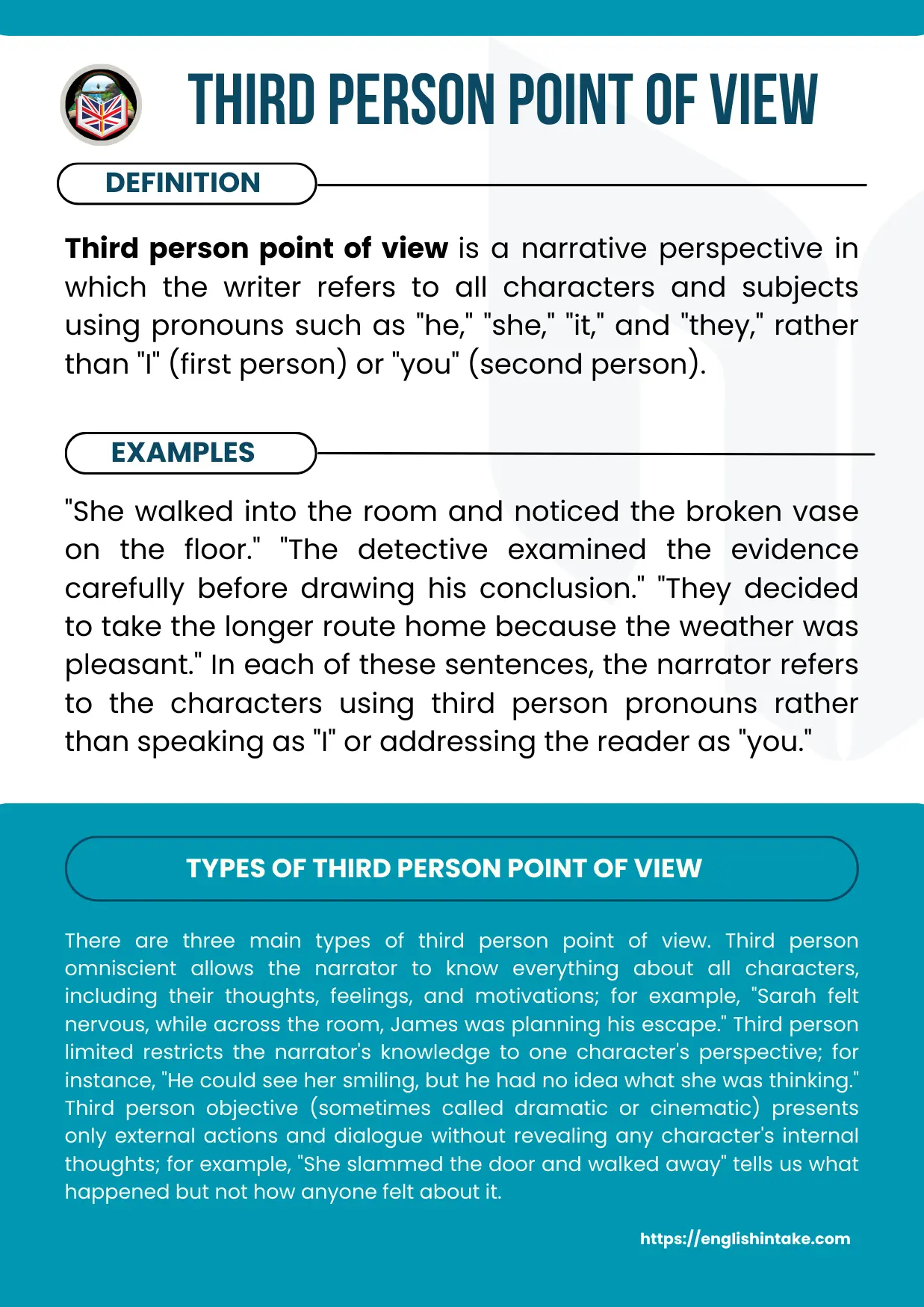

Third person point of view is a narrative perspective in which the writer refers to characters using pronouns such as he, she, it, and they, or by their names. Unlike first person point of view, where the narrator uses I and we, third person places the narrator outside the story rather than participating in them directly.

This perspective dominates both fiction and formal writing. In novels, it allows authors to follow characters through their journeys whilst maintaining some narrative distance. Like other literary devices that shape meaning and tone, it influences how readers interpret a story. In academic and professional writing, third person creates an objective, authoritative tone that keeps the focus on ideas rather than the writer's personal opinions.

2. Third person pronouns

To recognise the perspective, try to understand which pronouns belong to third person. See the table below to help you.

| Function | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Subject pronouns | he, she, it, one | they |

| Object pronouns | him, her, it, one | them |

| Possessive adjectives | his, her, its, one's | their |

| Possessive pronouns | his, hers, its | theirs |

| Reflexive pronouns | himself, herself, itself, oneself | themselves |

Note that they, them, and their can refer to a single person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant. This usage has become standard in contemporary English writing.

2.1 Examples of third person pronouns in sentences

Subject pronoun: She walked into the room and noticed the open window.

Object pronoun: The teacher handed him the assignment.

Possessive adjective: The cat licked its paw before settling into the cushion.

Possessive pronoun: The blue bicycle is hers.

Reflexive pronoun: Marcus found himself standing at the edge of the cliff, unsure how he had arrived there.

3. Types of third person point of view

Third person is not a single perspective but rather a family of related viewpoints. Each type offers different levels of access to characters' thoughts and different degrees of narrative distance. The three main types are omniscient, limited, and objective.

Writers choose between these based on what their story requires. A sprawling epic with dozens of characters might benefit from omniscient narration, whilst a psychological thriller might work better in limited third person, keeping readers confined to one character's perceptions.

4. Third person omniscient

In third person omniscient, the narrator knows everything. This all-knowing perspective can access any character's thoughts, reveal information no character possesses, and move freely through time and space. The word omniscient comes from the Latin omni (all) and sciens (knowing).

This perspective was particularly popular in nineteenth-century literature. Authors like Leo Tolstoy, George Eliot, and Charles Dickens used omniscient narration to create panoramic views of society, moving between characters' inner lives whilst offering commentary on human nature.

4.1 Characteristics of omniscient narration

The omniscient narrator typically has a distinct voice separate from any character's voice. This narrator can tell readers what multiple characters are thinking within a single scene, reveal background information characters do not know, and even address readers directly with observations or judgements about the story's events.

Consider this example: Margaret believed she had hidden her disappointment well, but Thomas noticed the slight tremor in her voice. Neither of them knew that their conversation was being observed from the garden below, where a decision was forming that would change both their lives forever.

4.2 Famous examples of third person omniscient

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen demonstrates how omniscient narration can create irony. The narrator sees beyond what characters perceive, allowing readers to understand Elizabeth Bennet's prejudices and Mr Darcy's pride before the characters themselves recognise these flaws.

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien uses omniscience to manage its vast scope, following multiple storylines across Middle-earth whilst maintaining a consistent narrative voice that feels almost like a chronicler recording history.

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak takes omniscient narration further by making Death itself the narrator; a perspective that is literally all-knowing about mortality and human fate.

5. Third person limited

Third person limited restricts the narrative to one character's perspective at a time. Readers experience the story through that character's senses, thoughts, and feelings, but the narration still uses third person pronouns. This creates intimacy similar to first person whilst maintaining some narrative flexibility.

This perspective dominates contemporary fiction. Most modern novels use third person limited because it balances character depth with storytelling flexibility.

5.1 How third person limited works

When writing in limited third person, the narrator can only reveal what the viewpoint character knows, sees, hears, and thinks. If Sarah is the viewpoint character, the narrator cannot tell readers what James is secretly planning unless Sarah somehow discovers it.

This limitation creates natural suspense. Readers discover information as the character does, making revelations more impactful. It also encourages writers to show other characters' emotions through observable behaviour rather than simply stating their feelings.

5.2 Famous examples of third person limited

The Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling follows Harry's perspective throughout most of the books. Readers know only what Harry knows, which is why Dumbledore's secrets and Snape's true loyalties remain mysterious for so long. This choice serves the mystery elements of the plot brilliantly.

George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series (adapted as Game of Thrones) uses multiple third person limited viewpoints, with each chapter following a different character. This approach lets readers see the same events from different angles whilst keeping each perspective contained.

6. Third person objective

Third person objective (sometimes called dramatic or cinematic point of view) presents only what can be observed externally. The narrator reports dialogue and actions but never enters any character's mind. Readers must infer thoughts and motivations from behaviour alone.

This perspective works like a camera recording a scene. It shows what characters say and do without explaining why. The effect is often detached, almost journalistic, forcing readers to interpret meaning themselves.

6.1 Famous examples of third person objective

Ernest Hemingway's short story Hills Like White Elephants exemplifies objective narration. The story presents a conversation between a man and woman at a train station, revealing nothing of their thoughts. Readers must deduce from their dialogue that they are discussing whether the woman should have an abortion; a word never spoken in the text.

This technique creates powerful ambiguity. Without access to characters' thoughts, readers engage more actively with the text, drawing their own conclusions about meaning and motivation.

7. Deep third person (or close third person)

Deep third person is an intensified version of limited third person that reads almost like first person narration. The narrative voice merges so closely with the character's consciousness that the distinction between narrator and character nearly disappears.

In deep third person, writers remove filter words like she thought, he felt, and she noticed. Instead of writing "She thought the room seemed cold," deep third person would render this as "The room was freezing" or simply describe her reaction to the temperature.

7.1 How deep POV differs from standard limited

Standard limited: Marcus wondered if he had made a mistake. He felt a knot forming in his stomach as he watched her walk away.

Deep third person: Had he made a mistake? His stomach twisted as she walked away. Of course he had. He always did.

The deep version removes the distance created by "wondered" and "felt," placing readers directly inside Marcus's experience. This technique has become increasingly popular in contemporary genre fiction, particularly romance and thrillers, where emotional immediacy drives reader engagement.

8. Head hopping: a common mistake

One of the most frequent errors writers make with third person is head hopping; jumping between characters' thoughts within a scene without clear transitions. This differs from omniscient narration, which maintains a consistent narrative voice above all characters.

Head hopping confuses readers because it disrupts the frame through which they experience the story. In one sentence, readers settle into Character A's perspective, then suddenly find themselves in Character B's head without warning. The effect is disorienting, like a camera that jerks between angles without purpose.

8.1 Head hopping versus omniscient narration

The key difference lies in the narrator's voice. In omniscient narration, a distinct narrative persona guides readers through different characters' thoughts. The narrator maintains consistency even whilst revealing multiple perspectives. In head hopping, there is no such guiding voice; the perspective simply lurches from one character to another.

Head hopping: Sarah couldn't believe Mark had lied to her. Mark knew she would find out eventually, but he couldn't help himself. Sarah's hands trembled with anger.

This shifts awkwardly from Sarah's perspective to Mark's and back again. An omniscient narrator would handle this differently, maintaining distance from both characters whilst revealing their thoughts.

8.2 How to avoid head hopping

If you are writing in limited third person, stick to one viewpoint character per scene. Use scene breaks (marked with white space or symbols like asterisks) when switching perspectives. Some authors change viewpoints only at chapter breaks, which provides the clearest signals to readers.

To convey what non-viewpoint characters are thinking, use external cues: body language, facial expressions, tone of voice, and dialogue. Instead of telling readers that James was nervous, show him fidgeting with his cuffs or avoiding eye contact.

9. Multiple POV in third person

Many novels use third person limited but follow several characters, switching between them at scene or chapter breaks. This approach offers some benefits of omniscient narration (multiple perspectives on events) whilst maintaining the intimacy of limited third person.

When done well, multiple POV creates a tapestry effect. Each character's chapter adds threads to the larger pattern, and readers gain satisfaction from holding knowledge that individual characters lack.

9.1 Tips for handling multiple viewpoints

Give each viewpoint character a distinct voice. Even though you are writing in third person, the narration should subtly reflect each character's vocabulary, concerns, and way of seeing the world. A scientist might notice technical details whilst an artist might perceive colours and textures.

Limit your number of viewpoint characters. Many writing guides suggest three to five viewpoint characters for a novel. Too many perspectives fragment reader attention and make it harder to build emotional investment in any single character.

10. Narrative distance in third person

Narrative distance (also called psychic distance) refers to how close readers feel to a character's thoughts and experiences. Third person offers a spectrum from very distant (objective) to very close (deep POV), and skilled writers modulate this distance throughout their work.

A chapter might begin with distant narration establishing setting, then gradually move closer as tension builds, finally plunging into deep POV during an emotional climax. This flexibility is one of third person's greatest strengths.

10.1 Levels of narrative distance

Distant: The city stretched beneath a grey November sky. In one of its many apartment buildings, a woman was preparing for a job interview.

Medium: Elena checked her reflection one more time. The interview started in an hour, and she still had not decided which shoes to wear.

Close: These shoes made her look professional but the heels would murder her feet. The black flats were comfortable but too casual. Why did everything have to be so complicated?

Each level has its uses. Distant narration works well for establishing shots and transitions; closer narration suits moments of tension, decision, or emotional significance.

11. Third person in academic and formal writing

Outside of fiction, third person serves different purposes. Academic writing typically uses third person to create an objective, authoritative tone. This perspective keeps focus on ideas and evidence rather than the writer's personal opinions.

Business and professional writing also favours third person. Reports, analyses, and formal correspondence generally avoid I and you to maintain professional distance.

11.1 When academic writing allows first person

Some academic contexts now permit or even encourage first person. Reflective essays, personal narratives within research papers, and certain disciplines (particularly some social sciences) accept first person when the writer's perspective is relevant to the analysis.

However, avoiding first person remains the default for most formal and academic contexts. Phrases like the researcher found or this study demonstrates maintain objectivity whilst keeping the prose clear.

12. Advantages of third person point of view

Third person offers flexibility that other perspectives cannot match. Writers can adjust narrative distance, follow multiple characters, and provide information beyond any single character's knowledge. This adaptability makes third person suitable for almost any type of story.

The perspective also creates opportunities for dramatic irony. Readers can know things characters do not, generating tension when audiences watch characters make decisions based on incomplete information.

12.1 Worldbuilding benefits

For stories requiring significant worldbuilding (fantasy, science fiction, historical fiction), third person allows more natural exposition. A first person narrator would need reasons to explain their own world, but a third person narrator can provide background information without such constraints.

Third person can be omniscient (allowing audiences to follow many characters) or limited (allowing access to only one or two important characters), giving writers significant control over how much readers know.

13. Challenges of third person point of view

Third person's flexibility can become a trap. Without careful attention, writers may accidentally shift perspectives, reveal information inconsistently, or lose the intimate connection that engages readers emotionally.

Maintaining consistent point of view requires discipline. Every sentence should be tested against the question: from whose perspective is this being told, and would that person know or perceive this?

13.1 Avoiding common pitfalls

Watch for accidental perspective shifts. If your viewpoint character cannot see their own facial expression, the narrator should not describe it (unless using omniscient narration). Similarly, your viewpoint character cannot know what another character is thinking unless that information is communicated through dialogue or action.

Avoid filter words that create unnecessary distance. Instead of writing "She saw the door was open," write "The door was open." The first version reminds readers they are observing a character observing something; the second places readers directly in the scene.

14. Comparing third person to other points of view

To help you choose the best perspective for your writing, make sure you understand the difference between first person, second person, and third person point of view.

First person offers maximum intimacy but limits information to what the narrator knows and chooses to share. Third person limited can achieve similar intimacy whilst offering more flexibility for exposition and scene-setting.

14.1 Third person versus first person

First person creates a direct relationship between narrator and reader. The narrator's voice is the character's voice, with all its limitations and biases. Third person, even at its closest, maintains some distinction between narrator and character.

This distinction matters for certain effects. An unreliable first person narrator can deceive readers directly; an unreliable character in third person limited requires more subtle handling because the narrator still exists separately from the character.

14.2 Third person versus second person

Second person (you walked into the room) creates an unusual relationship where readers become characters. This perspective appears occasionally in literary fiction and frequently in interactive fiction, but remains rare compared to first and third person.

Third person offers none of second person's direct reader involvement but also avoids its potential awkwardness. Second person risks alienating readers who resist being told what "they" are doing or feeling.

15. When to choose third person

Third person suits stories that need flexibility: multiple important characters, complex plots, significant worldbuilding, or shifts in narrative distance. It also works well when the author wants to maintain some aesthetic distance from the material.

If your story requires readers to know things your protagonist does not, third person (particularly omniscient) handles this naturally. If you want to follow multiple storylines that converge, multiple limited third person viewpoints offer an elegant solution.

Fantasy and science fiction frequently use third person for their worldbuilding advantages. Mystery and thriller writers often choose third person limited to control information flow whilst maintaining suspense. Literary fiction uses the full range of third person techniques depending on the specific work.

Romance novels increasingly use deep third person for emotional intensity, whilst epic fantasy often employs multiple POV to handle large casts. If you understand genre conventions, you can meet reader expectations whilst making informed choices about when to diverge from norms.